Geology of Great Bradley area

Like the vast majority of Suffolk, Great Bradley the surface 'rock' is the very fertile boulder clay or clay loam. This lies on top of layers of chalk.

Boreholes have shown that a river used to run and cut away the chalk underneath where Mill House is today. Sand and gravel were laid down in the valley. This was covered over by one of the ice ages with boulder clay. The retreating glaciers also left patches of gravel. Some of these are visible near for eg, Spring Barn, The Fox, The Old Rectory and where Kirtling Brook flows into the Stour. The current river course has lead to a alluvium deposits in the valley.

This area of the country was amongst the latest to be formed, during the Tertiary period (66 to 3 million years ago). It contains some of the youngest rock in the British Isles. The landscape surrounding Great Bradley is the result of the joint effects of past glaciation and the agricultural alteration of the land

Originally the area was under the sea. Over thousands of years the shells of the sea creatures dropped to bed of the ocean and formed into chalk about 140 million years ago. Another mineral, silica, filled the sponges and other similar animals in the sea. As this was left behind it formed nodules of hard flint. A ridge of chalk left by the ancient sea juts into Suffolk around Great Bradley from Cambridgeshire. This ridge is never more than 400 feet above sea level but it makes what is called High Suffolk. This chalk layer forms the so called solid rock layer. This chalk was originally quarried where it came to the surface, and was either burned to produce agricultural lime which was used as a top dressing or was mixed with sand, quarried locally, for mortar used in building (hence the presence of cream bricks for houses in the area). Clay lump was another use of boulder clay, and wattle-and-daub cottages had to be protected by a coating of lime plaster produced from the chalk. Information from boreholes have shown that this landscape was rather different from that of today, with a river cutting away the chalk beneath where Mill House now stands (first house on left hand side as you come into the village from Newmarket). Sand and gravel were laid down in the river's valley. The presence of the chalk in the water is why the water is so 'hard' (water for Great Bradley being drawn from a borehole in Great Wratting, on the left just past the pub).

Impact of the Ice Age

The first and the second ice ages had very little effect on the landscape of East Anglia. The third, however, happened approximately 780,000 years ago and lasted for some 90,000 years. Between this time and that of the last great glaciation to affect this area (the fourth), which took place between 235 and 360 thousand years ago the glaciers moved in from the north and brought with them a more rocky and patchy earth filled with stones and flints. This so called 'boulder clay' covers nearly the whole of Suffolk. It makes up the 'soil' in most of the land round Great Bradley. Some describe it as a clay loam, to distinguish it from the more heavy clay in central Suffolk. It is softly moulded into fertile swales or valleys just like the Stour Valley. The boulder clay covers a very large area and varies in thickness, usually between 30 and 50 metres. In this area thicknesses between 50 and 75 metres have been recorded. This boulder clay is referred to as the superficial or surface rock.

It was the presence of the boulder clay, with its thickness and its ability to be watertight when 'puddled', which persuaded the National River Authority to present a feasibility report in 1993 for a reservoir to be built at Great Bradley. But after opposition from all the local villages this proposal was rescinded in September 1995.

When the glaciers melted vast amounts of water were released, generally following the route of the streams and rivers that we see today. During this period the sea level was some 200 metres lower than it is today. This large amount of water had a great erosive power, carrying a vast quantity of debris and flowing beneath the glacier under high pressure, to produce tunnel valleys. Since these valleys were confined by the ice this caused the water to pass along deep incised water routes with irregular bases, before rising at the glacier snout to flow from the edge of the ice sheet as outwash or meltwater streams.

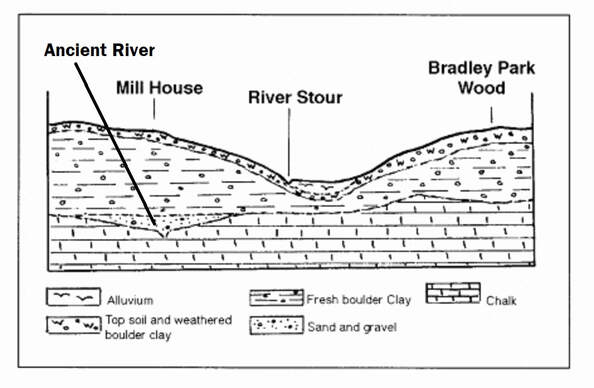

The cross-section below shows the village in the wide shallow valley of the Stour cut into the East Anglian plateau which gently dips toward the south - south east. This valley feature is the result of the advances and retreat of a glacier

Glacial sands and gravel are present the whole length of the River Stour. The bedrock in Great Bradley is some 20 metres below the present river level, the infill being mainly boulder clay with approximately 4 metres of glacial sands and gravel. The same tunnel valley that flowed through the area can be seen at Wixoe, where its lowest point is approximately 40 metres below the present sea level, while at Clare it is as far as 110 metres below our present sea level. Except for the tunnel valleys it is probable that the ice sheet, which produced the chalky boulder clay, rolled upon a bed of glacial sand and gravel, and also produced the general flattened character of the area which we see today.

Boreholes have shown that a river used to run and cut away the chalk underneath where Mill House is today. Sand and gravel were laid down in the valley. This was covered over by one of the ice ages with boulder clay. The retreating glaciers also left patches of gravel. Some of these are visible near for eg, Spring Barn, The Fox, The Old Rectory and where Kirtling Brook flows into the Stour. The current river course has lead to a alluvium deposits in the valley.

This area of the country was amongst the latest to be formed, during the Tertiary period (66 to 3 million years ago). It contains some of the youngest rock in the British Isles. The landscape surrounding Great Bradley is the result of the joint effects of past glaciation and the agricultural alteration of the land

Originally the area was under the sea. Over thousands of years the shells of the sea creatures dropped to bed of the ocean and formed into chalk about 140 million years ago. Another mineral, silica, filled the sponges and other similar animals in the sea. As this was left behind it formed nodules of hard flint. A ridge of chalk left by the ancient sea juts into Suffolk around Great Bradley from Cambridgeshire. This ridge is never more than 400 feet above sea level but it makes what is called High Suffolk. This chalk layer forms the so called solid rock layer. This chalk was originally quarried where it came to the surface, and was either burned to produce agricultural lime which was used as a top dressing or was mixed with sand, quarried locally, for mortar used in building (hence the presence of cream bricks for houses in the area). Clay lump was another use of boulder clay, and wattle-and-daub cottages had to be protected by a coating of lime plaster produced from the chalk. Information from boreholes have shown that this landscape was rather different from that of today, with a river cutting away the chalk beneath where Mill House now stands (first house on left hand side as you come into the village from Newmarket). Sand and gravel were laid down in the river's valley. The presence of the chalk in the water is why the water is so 'hard' (water for Great Bradley being drawn from a borehole in Great Wratting, on the left just past the pub).

Impact of the Ice Age

The first and the second ice ages had very little effect on the landscape of East Anglia. The third, however, happened approximately 780,000 years ago and lasted for some 90,000 years. Between this time and that of the last great glaciation to affect this area (the fourth), which took place between 235 and 360 thousand years ago the glaciers moved in from the north and brought with them a more rocky and patchy earth filled with stones and flints. This so called 'boulder clay' covers nearly the whole of Suffolk. It makes up the 'soil' in most of the land round Great Bradley. Some describe it as a clay loam, to distinguish it from the more heavy clay in central Suffolk. It is softly moulded into fertile swales or valleys just like the Stour Valley. The boulder clay covers a very large area and varies in thickness, usually between 30 and 50 metres. In this area thicknesses between 50 and 75 metres have been recorded. This boulder clay is referred to as the superficial or surface rock.

It was the presence of the boulder clay, with its thickness and its ability to be watertight when 'puddled', which persuaded the National River Authority to present a feasibility report in 1993 for a reservoir to be built at Great Bradley. But after opposition from all the local villages this proposal was rescinded in September 1995.

When the glaciers melted vast amounts of water were released, generally following the route of the streams and rivers that we see today. During this period the sea level was some 200 metres lower than it is today. This large amount of water had a great erosive power, carrying a vast quantity of debris and flowing beneath the glacier under high pressure, to produce tunnel valleys. Since these valleys were confined by the ice this caused the water to pass along deep incised water routes with irregular bases, before rising at the glacier snout to flow from the edge of the ice sheet as outwash or meltwater streams.

The cross-section below shows the village in the wide shallow valley of the Stour cut into the East Anglian plateau which gently dips toward the south - south east. This valley feature is the result of the advances and retreat of a glacier

Glacial sands and gravel are present the whole length of the River Stour. The bedrock in Great Bradley is some 20 metres below the present river level, the infill being mainly boulder clay with approximately 4 metres of glacial sands and gravel. The same tunnel valley that flowed through the area can be seen at Wixoe, where its lowest point is approximately 40 metres below the present sea level, while at Clare it is as far as 110 metres below our present sea level. Except for the tunnel valleys it is probable that the ice sheet, which produced the chalky boulder clay, rolled upon a bed of glacial sand and gravel, and also produced the general flattened character of the area which we see today.

With the ice melted, early rivers left gravel patches in areas of the clay. Some of the last of these show on the surface in Great Bradley, for instance near Spring Barn (the last houses out of the village on the left, going to Thurlow), The Fox and the Old Rectory at the Newmarket end of the village. The gravel can also be seen to the north east where the stream flows from Kirtling to the River Stour.

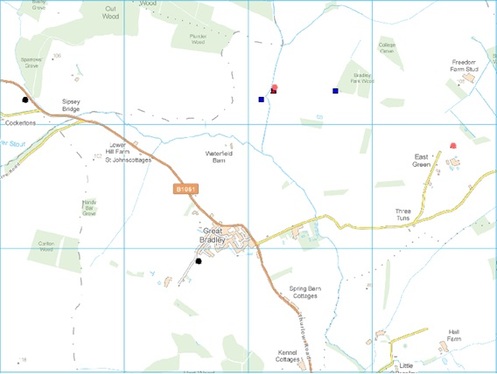

Map showing clay and gravel deposits near the surface on top of a chalk bedrock

The River Stour has shaped the present landscape. It is 47 miles (76km) long and Great Bradley is the first village along its length. Variations in climate and sea level over the past twelve thousand years or so mean that our river has varied greatly in size, and is possibly as small now as it ever has been.

The hills and valleys of Great Bradley have been scoured by rain, stream and river to form the parish where we live. Since 1954, rainfall in Great Bradley has been recorded at Great Bradley Hall. Annual rainfall has been 20" - 30" per year, with the wettest year being 2013 (35") and the driest, 1964 (17.62").

Although we are fairly low lying for the UK Great Bradley is quite high for Suffolk. There is a trig point at East Green, on the land occupied by the Bradley Oak Stud. It is recorded at 107 metres or 351 feet above sea level. This is 20m (65 feet) lower than the highest point in Suffolk, at Rede, but higher than any point in Norfolk!

Map showing clay and gravel deposits near the surface on top of a chalk bedrock

The River Stour has shaped the present landscape. It is 47 miles (76km) long and Great Bradley is the first village along its length. Variations in climate and sea level over the past twelve thousand years or so mean that our river has varied greatly in size, and is possibly as small now as it ever has been.

The hills and valleys of Great Bradley have been scoured by rain, stream and river to form the parish where we live. Since 1954, rainfall in Great Bradley has been recorded at Great Bradley Hall. Annual rainfall has been 20" - 30" per year, with the wettest year being 2013 (35") and the driest, 1964 (17.62").

Although we are fairly low lying for the UK Great Bradley is quite high for Suffolk. There is a trig point at East Green, on the land occupied by the Bradley Oak Stud. It is recorded at 107 metres or 351 feet above sea level. This is 20m (65 feet) lower than the highest point in Suffolk, at Rede, but higher than any point in Norfolk!

The map below shows the sites of the boreholes used by the British Goelogical Survey to gain relevant information