Farming in Great Bradley during WWII

|

Bill Cowans, who was a young man on his father's farm at East Green, Great Bradley, at the outbreak of War, has these recollections on the following three subjects:

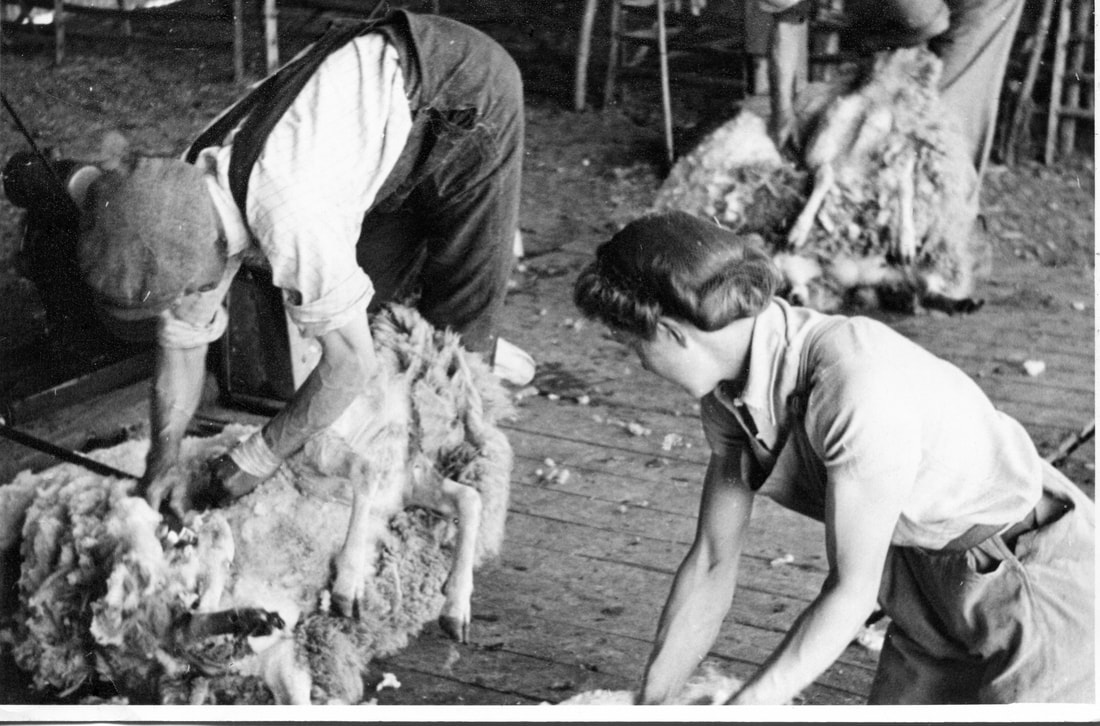

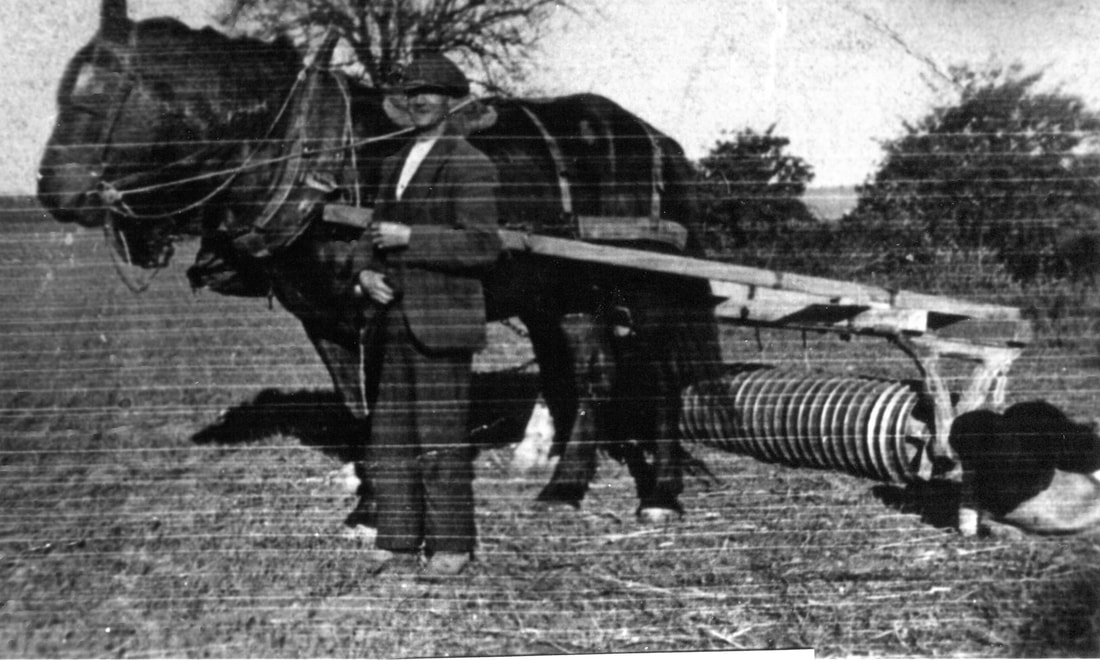

Prisoners of War 'Agriculture in East Anglia had been in decline during the Thirties and it was only the outbreak of War in 1939 that revived its fortunes. Food had to be produced at home, and it soon became clear that Prisoners of War (POWs) would play an important part in providing labour for this task. The first POWs to appear in the area were Italians captured in the Middle East campaign. They were camped at various places in Suffolk; the one that comes to mind, and I believe one of the largest, was Brandon. Gangs of Italians were transported daily to farms to carry out specific tasks, e.g. potato picking and sugar beet lifting, all work that was done by hand in those days. They were brought in lorries - ten or twelve in a gang, with a civilian driver and, at first, an armed soldier although, later on, the guard was dropped and the driver had responsibility for them. They proved on the whole to be lazy, although, there were notable exceptions. All however, were very adept at making small toys, brooches, etc, from next to nothing and cigarette lighters from empty shell cases. Stealing hens' eggs and anything else edible was a speciality aided and abetted by the civilian driver The gang scheme was soon reduced in favour of putting trusted and reliable prisoners out on to farms to live and work. So it was that we had Henry and Paulo to live at my father's farm. East Green Farm in, I think, 1942. They lived in the Farm House, sleeping in the attic rooms. Henry was the elder of the two, and the better worker. Paulo was a fascist and a bit of an agitator, and was eventually sent back to camp. The Italians left after about a year to be replaced by German and Austrian POWs. Three came to East Green and were installed in an old empty farm cottage. We were responsible for them, and they were confined to a small area around the farm. We provided their food, which they cooked themselves, and other small luxuries. They were returned to camp once a month to pick up any toiletries, change clothing, letters from home, etc, that they required. Henry, Hajo and Willy had all been engaged in farming in Germany soon proved to be trustworthy, honest and very hard working. My father said that Hajo was the best stockman that was ever at East Green. Consequently, they received a lot of 'extras' from my mother, and soon were part of the family! Henry could ride a horse when he came, and was soon to be seen riding a long way outside the restricted area. My father's horse had been seen tied up outside the Red Lion in Kirtling on a number of occasions, although Henry always denied it with a grin on his face! They stayed with us until repatriation in late 1945. Visits to their camp were abandoned early on, when they persuaded their families to write direct to them at East Green, and my mother provided and looked after me necessities for them! A phone call to the camp once a month to assure the authorities that they had not escaped seemed to satisfy all concerned. We kept in touch with them for a while on their return home, (see letter below) and my wife and I visited Henry at his home in North West Germany on one occasion. "Bokelesch, January 11, 1948 My Dear Family Cowans I will send you a letter now, I had no time before. Everything is getting along fine here, hoping the same from you and yours. I left Great Britain the 16 of December 1947 and arrived at my home in December 22, 1947, 9 o'clock in the morning. I was happy that I found my people and home alright and so I had a nice Christmas with my family, it was too nice and too happy for everyone of us. Many men visited me and all day - were men come in to talk to me, but it is alright, than I'm still in follow and I enjoy this time. The weather is colder here than over there, and we have snowstorm and high water. What is going on with your cows, hens and so forth? Hoping to hear from you real soon and wishing you the best of luck. I am your friend, Hajo and wife." Austrian POWs worked on Great Bradley Hall farm during the same period and lived in a house that stood on the site of Sugar Loaf. One of these had been a butcher back home, and soon became called upon to slaughter pigs in the area. I can remember him slaughtering several at East Green, and he returned to the area twice after the War and paid us a visit. POWs must have contributed quite a lot to the production of food during the War. They and the Women’s Land Army virtually provided all the labour force on several farms during that period.' Women's Land Army 'The Women's Land Army was originally formed during me First World War in 1914/15 and had proved to be very useful in providing labour for farms during mat period. It was re-formed during World War II in, I think, 1940 and soon its members were a familiar sight in me countryside dressed in their uniform of fawn breeches, green jumpers, and round brimmed hats. There were three kinds of Land Girl: the volunteer who found their own jobs and lived on the farm or locally in their own accommodation. Normally, these were local girls who worked on neighbouring farms. those who were directed to land work and lived in hostels, and could be sent anywhere to work. those who were directed to forestry work and again lived in hostels. This proved to be very heavy work. A mother and daughter came to live in Thurlow to escape the bombing in London, and Penelope soon came to work at East Green as a Volunteer Land Girl. She was a very intelligent girl and despite having no experience of farm work or countryside living, soon fitted in very well, and became good at looking after livestock. It must have been a terrible culture shock for her, having been engaged in Public Relations in London. The existing staff reacted in two ways to the presence of a female working on the farm. Some thought it was great having a girl with them all day, whilst the older ones thought a woman, especially a Londoner, had no place in the country. However, they all eventually accepted that she was doing a good job. Penelope, wrapping fleeces to be sold to the merchant Some six months after arriving, Penelope asked if her sister could join her at East Green. Susanne was a beauty consultant in a large store in London, and on arrival was dressed to kill, with lavish make-up, nail varnish, etc. She took to farm life even more easily than her sister, and of course there was competition between the male members of staff as to who should work with her! One of her tasks was to feed the Bull each day. The animal was housed in a small building, access to which was through a passage of very wet and deep mud (there was very little concrete on farms in those days). Susanne was proceeding along the passsage thinking what she would be like if the Bull escaped; no sooner had these thoughts occurred, when the door opened and the Bull stepped out. Susanne jumped straight out of her Wellingtons into the slimy mud. Both sisters stayed at East Green for the rest of the war. Several girls also worked at Great Bradley Hall where there was a large dairy herd. Some were local girls, but I believe there were three or four others who were directed to work and lodged at Fox Farmhouse. At the same time. Little Bradley House was taken over and converted into a hostel for Land Girls. They worked on various farms in the area and, I believe, some of them were engaged in Forestry. Romance, of course, blossomed with local lads as well as servicemen that were stationed in the area. At least two local men married Land Army Girls during the War. The Land Army was disbanded at the end of the War, each member receiving a certificate from Queen Elizabeth, the present Queen Mother, thanking them for their service.' Farming at East Green in Wartime 'Canadian Wheat was the chief source of supply for United Kingdom millers in the thirties, mainly because of its guaranteed quality and cheapness and this was one of the reasons for recession in our farming industry prior to the outbreak of War. It soon became clear that, at best, Canadian and American Wheat supplies would be reduced and, at worst, be cut off completely. With the U-boat campaign in the Atlantic, this prophesy soon became reality, and the Government decided to take control of farm output. War Agricultural committees were set up in every county to control farming and these committees consisted of Ministry of Agriculture officials and prominent local farmers. Their brief was to increase production of grain to offset the loss of imports. The idea was to leave livestock farming to the hill areas and land that could not be ploughed. East Anglia was largely unaffected, since it was already an arable area and had grown grain for many years. However, large areas of the Midlands and South West had been predominantly grass farms, and were made to plough and go over to grain production. East Green farm had been put down to grass in the early thirties and was therefore an exception to the rule in Suffolk. It was a livestock farm with about 400 breeding sheep and around 150 cattle, with just a small acreage set aside to grow feed for the animals. For this reason, it was soon the target of the 'War Ags', as the committees became known in the farming community. They had great powers, controlling every aspect of farm operations, including the crops to grow, labour, permits for machinery purchase , fuel distribution, etc. They had the authority to evict farmers if they thought they were not complying. The acreage to be ploughed at East Green was increased year by year, until some 75-80% of the farm was growing arable crops by the end of the War. It was a difficult time, since very hide machinery was owned at the onset, with that already on the farm being out-dated and horse drawn. Tractors were just beginning to take over from the horse, but were in short supply. However, the Ford Motor Company was directed to produce the Fordson tractor in larger numbers, and soon appeared at East Green. A lot of work , including the initial ploughing, was done by contract. Gradually, American tractors and machinery began to arrive, and one of the first contractors to use them were Turner and Hove of Newmarket (now Heath Ford Garage). The Minneapolis Moline Tractor was a large yellow machine on steel wheels, and it shook you to bits when driving it! 1942 Fordson Tractor Every kind of arable crop was grown at East Green - Wheat, Barley, Oats, Sugar Beet, Potatoes, Mangles and Linseed. Despite increased machinery availability, there was still a need for lots of labour and at one time mere were twenty people working on the farm plus occasional gangs for seasonal work, e.g. sugar beet lifting and potato picking. POWs were also used together with labour groups supplied by the War Ags. Soon it was decided that a tracked tractor was needed to do the heavy work on the farm. The War Ag agreed, and a permit issued. Unfortunately, none were available and we had to wait for a shipment from the USA. Eventually, we were notified that a load was due on a certain date at Ipswich Docks and that our tractor could be collected from there, but on entering the mouth of the River Orwell, the ship struck a mine and was sunk. It was some considerable time before the next shipload arrived and we got our tractor. Combine Harvesters appeared during the War, again all American. The first to arrive at East Green was an MM and was a tractor-drawn machine as opposed to self-propelled as today's are. It was in kit form, in large packing cases, and was assembled on the farm by staff and a fitter from the suppliers. It took all weekend and the machine was working on the Monday. The grain was bagged on the machine, and three or four at a time were slid off the combine, to be picked up later on trailers. There were no chemical weed killers during the War, and hand hoeing of crops was carried out. However this was not always successful, and I remember one year, some barley crops were full of a weed called Charlock. During the cleaning operation after harvest, the Charlock seed was removed, and my father was delighted when he found he could sell the Charlock seed for Bird Feed at a price nearly as high as the barley itself! Livestock numbers, of course, had to be reduced, but I think we still kept about 250 sheep and 70 to 100 came. A small number of pigs were also introduced, mainly to supply ourselves with Pork, Ham and Bacon! Hens of course, were kept to supply us with eggs. With the end of War, restrictions were gradually lifted, and although some land was returned to grass, a fairly large proportion of East Green remained arable, and it never again became an all grass, livestock farm.' |

|